The word ‘leadership’ is highlighted in both EAB’s mission and vision statements and represents a key element of our school’s educational program. To implement the leadership component, EAB offers students and teachers a variety of leadership opportunities and learning experiences that foster a culture where community members embrace, excel, and are supported in their leadership roles.

As part of the educational program, students engage in leadership roles through student council positions, enrollment in leadership classes, committees and teams, public speaking and presentation opportunities, the student enrichment program, among many other examples. The concept of leadership development is also modeled by teachers through, for example, their roles in coordinating student activities, coaching, and serving as the heads of committees and focus groups. To further model development and ensure a greater distribution of leadership at EAB, a Leadership Essentials course is offered to faculty and administrators this year to study the theoretical and practical aspects of leadership.

In summary, the development of strong and effective leadership skills in our community is an essential ability that is highlighted through EAB’s mission, vision, and educational and professional programs.

To conclude, I would like to share a recent article by leadership guru, Jim Collins, who highlights an important aspect of leadership through his article titled, How to Manage Through Chaos, which is derived from his book, “Great by Choice.“ The article uses the metaphor of the “20-mile march” as an approach to steady and effective progress and a critical factor associated with successful leadership. I hope the article serves as a source of reflection for both your personal context and that of EAB’s ongoing development.

Jim Collins: How to Manage Through Chaos

This article is from the October 17, 2011 issue of Fortune

Perhaps the most influential management thinker alive, Jim Collins addressed the reasons companies succeed and fail in bestselling books like Good to Great and Built to Last. In their new book, Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos and Luck — Why Some Thrive Despite Them All, Collins and co-author Morten T. Hansen studied leadership in turbulent times, a topic they chose in 2002 that could not be more relevant today. Below, an exclusive excerpt:

We cannot predict the future. But we can create it.

Think back to 15 years ago, and consider what’s happened since, the destabilizing events — in the world, in your country, in the markets, in your work, in your life — that defied all expectations. We can be astonished, confounded, shocked, stunned, delighted, or terrified, but rarely prescient. None of us can predict with certainty the twists and turns our lives will take. Life is uncertain, the future unknown.

We began the nine-year research project behind this book in 2002, when America awoke from its false sense of stability, safety, and wealth entitlement. The long-running bull market crashed. The government budget surplus flipped back to deficits. The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, horrified and enraged people everywhere, and war followed. Meanwhile, throughout the world, technological change and global competition continued their relentless, disruptive march. It led us to a simple question: Why do some companies thrive in uncertainty, even chaos, and others do not? When buffeted by tumultuous events, when hit by big, fast-moving forces that we can neither predict nor control, what distinguishes those who perform exceptionally well from those who underperform or worse?

We don’t choose study questions. They choose us. Sometimes one of the questions just grabs us around the throat and growls, “I’m not going to release my grip and let you breathe until you answer me!” This study grabbed us because of our own persistent angst and gnawing sense of vulnerability in a world that feels increasingly disordered.

Yet some companies and leaders navigate this type of world exceptionally well. They don’t merely react; they create. They don’t merely survive; they prevail. They don’t merely succeed; they thrive. They build great enterprises that can endure. We do not believe that chaos, uncertainty, and instability are good; companies, leaders, organizations, and societies do not thrive on chaos. But they can thrive in chaos.

To get at the question of how, we embarked upon an ambitious journey to identify and study a select group of companies that had done just that. We set out to find companies that started from a position of vulnerability, rose to become great companies with spectacular performance, and did so in unstable environments characterized by big forces, out of their control, fast-moving, uncertain, and potentially harmful. We then compared these companies to a control group of companies that failed to become great in the same extreme environments, using the contrast between winners and also-rans to uncover the distinguishing factors that allow some to thrive in uncertainty.

From an initial list of 20,400 companies, we sifted through 11 layers of cuts to identify cases that met all our tests (our study era ran through 2002). Only seven did. We labeled our high-performing study cases with the moniker “10X” because they didn’t merely get by or just become successful. They truly thrived. Every 10X case beat its industry index by at least 10 times. Consider one 10X case, Southwest Airlines (LUV). Just think of everything that slammed the airline industry from 1972 to 2002: Fuel shocks. Deregulation. Labor strife. Air-traffic controller strikes. Crippling recessions. Interest rate spikes. Hijackings. Bankruptcy after bankruptcy after bankruptcy. And in 2001, the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11. And yet if you’d invested $10,000 in Southwest Airlines on Dec. 31, 1972 (when it was just a tiny little outfit with three airplanes, barely reaching breakeven and besieged by larger airlines out to kill the fledgling), your $10,000 would have grown to nearly $12 million by the end of 2002, a return 63 times better than the general stock market. These are impressive results by any measure, but they’re astonishing when you take into account the roiling storms, destabilizing shocks, and chronic uncertainty of Southwest’s environment. Meanwhile, Southwest’s direct comparison, Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA), flailed and was rendered irrelevant, despite having the same business model in the same industry with the same opportunity to become great.

Why did the 10X companies achieve such spectacular results, especially when direct comparisons — companies operating in the same fast-moving, unpredictable, and tumultuous environments — did not? Part of the answer lies in the distinctive behaviors of their leaders.

Are you an Amundsen or a Scott?

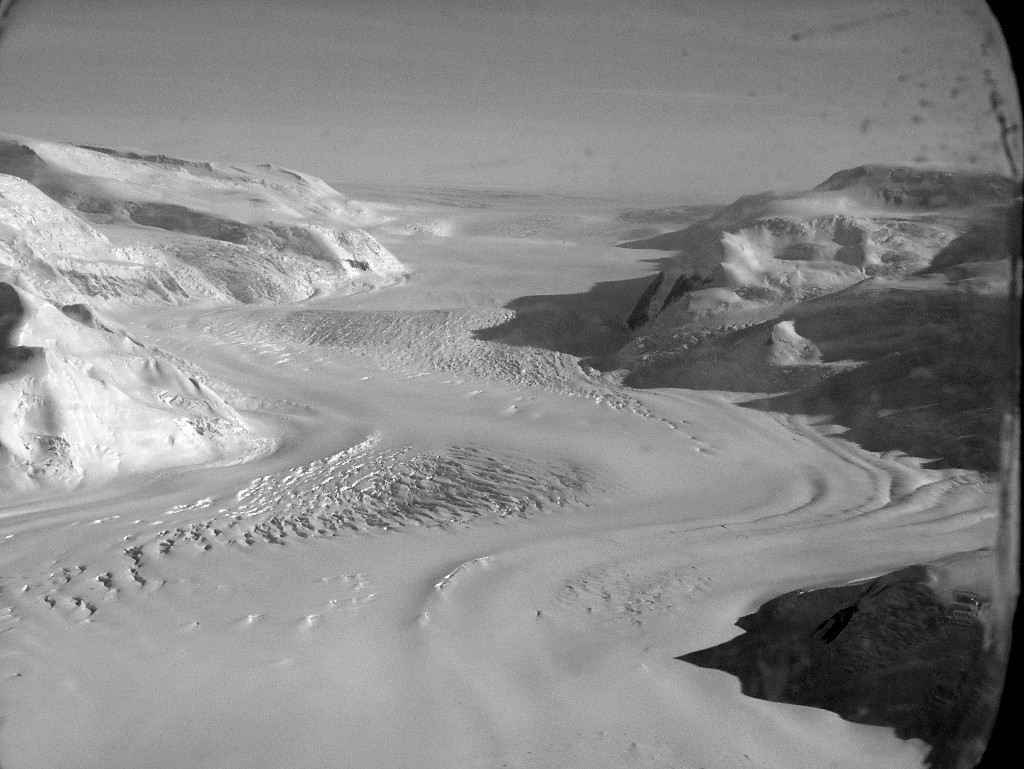

In October 1911, two teams of adventurers made their final preparations in their quest to be the first people in modern history to reach the South Pole. For one team, it would be a race to victory and a safe return home. For the second team, it would be a devastating defeat, reaching the Pole only to find the wind-whipped flags of their rivals planted 34 days earlier, followed by a race for their lives — a race that they lost in the end, as the advancing winter swallowed them up. All five members of the second Pole team perished, staggering from exhaustion, suffering the dead-black pain of frostbite, and then freezing to death as some wrote their final journal entries and notes to loved ones back home.

It’s a near-perfect matched pair. Here we have two expedition leaders — Roald Amundsen, the winner, and Robert Falcon Scott, the loser — of similar ages (39 and 43) and with comparable experience. Amundsen and Scott started their respective journeys for the Pole within days of each other, both facing a roundtrip of more than 1,400 miles into an uncertain and unforgiving environment, where temperatures could easily reach 20˚ below zero even during the summer, made worse by gale-force winds. And keep in mind, this was 1911. They had no means of modern communication to call back to base camp — no radio, no cellphones, no satellite links — and a rescue would have been highly improbable at the South Pole if they screwed up. One leader led his team to victory and safety. The other led his team to defeat and death.

What separated these two men? Why did one achieve spectacular success in such an extreme set of conditions, while the other failed even to survive? It’s a fascinating question and a vivid analogy for our overall topic. Here we have two leaders, both on quests for extreme achievement in an extreme environment. And it turns out that the 10X business leaders in our research behaved very much like Amundsen and the comparison leaders behaved much more like Scott.

The Colvin interview: Jim Collins in his own words

Amundsen and Scott achieved dramatically different outcomes not because they faced dramatically different circumstances. In the first 34 days of their respective expeditions, according to Roland Huntford in his superb book The Last Place on Earth, Amundsen and Scott had exactly the same ratio, 56%, of good days to bad days of weather. If they faced the same environment in the same year with the same goal, the causes of their respective success and failure simply cannot be the environment. They had divergent outcomes principally because they displayed very different behaviors.

So, too, with the leaders in our research study. Like Amundsen and Scott, our matched pairs were vulnerable to the same environments at the same time. Yet some leaders proved themselves to be 10Xers while leaders on the other side of the pair did not.

Let’s first look at what we did not find about 10Xers relative to their less successful comparisons: They’re not more creative. They’re not more visionary. They’re not more charismatic. They’re not more ambitious. They’re not more blessed by luck. They’re not more risk-seeking. They’re not more heroic. And they’re not more prone to making big, bold moves. To be clear, we’re not saying that 10Xers lacked creative intensity, ferocious ambition, or the courage to bet big. They displayed all these traits, but so did their less successful comparisons.

So then, how did the 10Xers distinguish themselves? First, they embrace a paradox of control and noncontrol. On the one hand, 10Xers understand that they face continuous uncertainty and that they cannot control, and cannot accurately predict, significant aspects of the world around them. On the other hand, they reject the idea that forces outside their control or chance events will determine their results; they accept full responsibility for their own fate.

10Xers then bring this idea to life by a triad of core behaviors: fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia. And they all led their teams with a surprising method of self-control in an out-of-control world.

The 20-Mile March

Imagine you’re standing with your feet in the Pacific Ocean in San Diego, looking inland. You’re about to embark on a 3,000-mile walk, from San Diego to the tip of Maine. On the first day you march 20 miles, making it out of town.

On the second day you march 20 miles. And again, on the third day you march 20 miles, heading into the heat of the desert. It’s hot, more than 100˚F, and you want to rest in the cool of your tent. But you don’t. You get up and you march 20 miles.

You keep the pace, 20 miles a day.

Then the weather cools, and you’re in comfortable conditions with the wind at your back, and you could go much farther. But you hold back, modulating your effort. You stick with your 20 miles.

Then you reach the Colorado high mountains and get hit by snow, wind, and temperatures below zero — and all you want to do is stay in your tent. But you get up. You get dressed. You march your 20 miles.

You keep up the effort — 20 miles, 20 miles, 20 miles — then you cross into the plains, and it’s glorious springtime, and you can go 40 or 50 miles in a day. But you don’t. You sustain your pace, marching 20 miles.

And eventually, you get to Maine.

Now, imagine another person who starts out with you on the same day in San Diego. He gets all excited by the journey and logs 40 miles the first day.

Exhausted from his first gigantic day, he wakes up to 100˚ temperatures. He decides to hang out until the weather cools, thinking, “I’ll make it up when conditions improve.” He maintains this pattern — big days with good conditions, whining and waiting in his tent on bad days — as he moves across the western United States.

Just before the Colorado high mountains, he gets a spate of great weather and he goes all out, logging 40- to 50-mile days to make up lost ground. But then he hits a huge winter storm when utterly exhausted. It nearly kills him and he hunkers down in his tent, waiting for spring.

When spring finally comes, he emerges, weakened, and stumbles off toward Maine. By the time he enters Kansas City, you, with your relentless 20-mile march, have already reached the tip of Maine. You win, by a huge margin.

Jim Collins’s Steady Seven

Now, think of medical-equipment maker Stryker as a 20-Mile March company.

When John Brown became CEO of Stryker (SYK) in 1977, he deliberately set a performance benchmark to drive consistent progress: Stryker would achieve 20% net income growth every year. This was more than a mere target, or a wish, or a hope, or a dream, or a vision. It was, to use Brown’s own words, “the law.” He ingrained “the law” into the company’s culture, making it a way of life. (Twenty percent may seem like a high bar, but for a small company in an explosive industry, it was achievable.)

Brown created the “Snorkel Award,” given to those who lagged behind; 20% was the watermark, and if you were below it, you needed a snorkel. Just imagine receiving a mounted snorkel from John Brown to hang on your wall so everyone can see that you’re in danger of drowning. People worked hard to keep the snorkel off their walls.

Stryker’s annual division-review meetings included a chairman’s breakfast. Those who hit their 20-Mile March went to John Brown’s breakfast table. Those who didn’t went to another breakfast. “They are well fed,” said Brown, “but it is not the one where you want to go.”

If your division fell behind for two years in a row, Brown would insert himself to “help,” working around the clock to “help” you get back on track. “We’ll arrive at an agreement as to what has to be done to correct the problem,” said the understated Brown. You get the distinct impression that you really don’t want to need John Brown’s help. According to Investor’s Business Daily, “John Brown doesn’t want to hear excuses. Markets bad? Currency exchange rates are hurting results? Doesn’t matter.” Describing challenges Stryker faced in Europe due partly to currency exchange rates, an analyst noted, “It’s hard to know how much of [the problem] was external. But at Stryker, that’s irrelevant.”

From the time John Brown became CEO in 1977 through 1998 (when its comparison, USSC, disappeared as a public company), and excluding a 1990 extraordinary gain, Stryker hit its 20-Mile March goal more than 90% of the time. Yet for all this self-imposed pressure, Stryker had an equally important self-imposed constraint: to never go too far, to never grow too much in a single year. Just imagine the pressure from Wall Street to increase growth when your direct rival is growing faster than your company. In fact, Stryker grew more slowly than USSC more than half the time. According to the Wall Street Transcript, some observers criticized Brown for not being more aggressive. Brown, however, consciously chose to maintain the 20-Mile March, regardless of criticism urging him to grow Stryker at a faster pace in boom years.

John Brown understood that if you want to achieve consistent performance, you need both parts of a 20-Mile March: a lower bound and an upper bound, a hurdle that you jump over and a ceiling that you will not rise above, the ambition to achieve and the self-control to hold back.

Southwest’s radical restraint

When we began this study, we thought we might see 10X winners respond to a volatile, fast-changing world full of new opportunities by pursuing aggressive growth and making radical, big leaps, catching and riding the Next Big Wave, time and again. And yes, they did grow, and they did pursue spectacular opportunities as they grew. But the less successful comparison cases pursued much more aggressive growth and undertook big-leap, radical-change adventures to a much greater degree than the 10X winners. The 10X cases exemplified what we came to call the 20-Mile March concept, hitting stepwise performance markers with great consistency over a long period of time, and the comparison cases did not.

The 20-Mile March is more than a philosophy. It’s about having concrete, clear, intelligent, and rigorously pursued performance mechanisms that keep you on track. The 20-Mile March creates two types of self-imposed discomfort: (1) the discomfort of unwavering commitment to high performance in difficult conditions, and (2) the discomfort of holding back in good conditions.

Southwest Airlines, for example, demanded of itself a profit every year, even when the entire industry lost money. From 1990 through 2003, the U.S. airline industry as a whole turned a profit in just six of 14 years. In the early 1990s it lost $13 billion and furloughed more than 100,000 employees; Southwest remained profitable and furloughed not a single person. Despite an almost chronic epidemic of airline troubles, including high-profile bankruptcies of some major carriers, Southwest generated a profit every year for 30 consecutive years.

Equally important, Southwest had the discipline to hold back in good times so as not to extend beyond its ability to preserve profitability and the Southwest culture. It didn’t expand outside Texas until nearly eight years after starting service, making a small jump to New Orleans. Southwest moved outward from Texas in deliberate steps — Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Albuquerque, Phoenix, Los Angeles — and didn’t reach the Eastern Seaboard until almost a quarter of a century after its founding. In 1996 more than 100 cities clamored for Southwest service. And how many cities did Southwest open that year? Four.

At first glance, this might not strike you as particularly significant. But stop to think about it. Here we have an airline setting for itself a standard of consistent performance that no other airline achieves. Anyone who said they’d be profitable every year for nearly three decades in the airline business — the airline business! — would be laughed at. No one does that. But Southwest did. Here also we have a publicly traded company willing to leave growth on the table. How many business leaders of publicly traded companies have the ability to leave gobs of growth on the table, especially during boom times when competitors do not leave growth on the table? Few, indeed. But Southwest did that too.

Some people believe that a world characterized by radical change and disruptive forces no longer favors those who engage in consistent 20-Mile Marching. Yet the great irony is that when we examined just this type of out-of-control, fast-paced environment, we found that every 10X company — unlike their less-successful peers — exemplified the 20-Mile March principle during the era we studied.

Progressive’s marching mantra

In the early 1970s, Progressive Insurance CEO Peter Lewis articulated a stringent performance metric: Progressive should grow only at a rate at which it could still sustain exemplary customer service and achieve a profitable “combined ratio” averaging 96%. What does a combined ratio of 96% mean? If you sell $100 of insurance, you should need to pay out no more than $96 in losses plus overhead combined. The combined ratio captures the central challenge for the insurance business, pricing premiums at a rate that’ll allow you to pay out on losses, service customers, and earn a return. If a company lowers prices to increase growth, its combined ratio could deteriorate. If it misjudges risks or mismanages its claims service, its combined ratio will suffer. If the combined ratio climbs over 100%, the company loses money on its insurance business.

Progressive’s “profitable combined ratio” mantra became like John Brown’s 20% law, a rigorous standard to accomplish year in and year out. Progressive’s stance: If competitors lower rates in an unprofitable bid to increase share — fine, let them do so! We will not chase them into senseless self-destruction. Progressive had an unequivocal commitment to the profitable combined ratio, no matter what conditions it faced, how its competitors behaved, or what seductive growth opportunities beckoned. Said Lewis in 1972: “There is no excuse, not regulatory problems, not competitive difficulties, not natural disaster, for failing to do so.” Progressive achieved a profitable combined ratio 27 out of 30 years, 1972-2002, and averaged just better than its 96% target.

Do you need to accomplish your 20-Mile March with 100% success? Progressive and its fellow 10X companies didn’t have a perfect record, only a near-perfect record, but they never saw missing a march as “okay.” If they missed it even once, they obsessed over what they needed to do to get back on track: There’s no excuse, and it’s up to us to correct for our failures, period.

The 20-Mile March imposes order amid disorder, consistency amid swirling inconsistency. But it works only if you actually achieve your march year after year. If you set a 20-Mile March and then fail to achieve it — or worse, abandon fanatic discipline altogether — you may well get crushed by events.

Why 20-Mile Marchers win

Twenty-Mile Marching helps turn the odds in your favor for three reasons. First, it builds confidence in your ability to perform well in adverse circumstances. Confidence comes not from motivational speeches, charismatic inspiration, wild pep rallies, unfounded optimism, or blind hope. Taciturn, understated, and reserved, John Brown at Stryker avoided all of that. Stryker earned its confidence by actual achievement, accomplishing stringent performance standards year in and year out, no matter the industry conditions. Accomplishing a 20-Mile March, consistently, in good times and bad, builds confidence. Tangible achievement in the face of adversity reinforces the 10X perspective: We are ultimately responsible for improving performance. We never blame circumstance; we never blame the environment.

Second, 20-Mile Marching reduces the likelihood of catastrophe when you’re hit by turbulent disruption. In a setting characterized by unpredictability, full of immense threat and opportunity, you cannot afford to leave yourself exposed to unforeseen events. If you’re hiking in the warm, comfortable glow of a spring day on a nice, wide, wandering trail near your home, you can overextend yourself and you might need to take two Advil to soothe your sore muscles when you’re done. But if you’re climbing in the Himalayas or journeying to the South Pole, going too far can have much more severe consequences from which you might never recover. You can get away with failing to 20-Mile March in stable times for a while, but doing so leaves you weak and undisciplined, and therefore exposed when unstable times come. And they will always come.

Third, 20-Mile Marching helps you exert self-control in an out-of-control environment.

On Dec. 12, 1911, Amundsen and his team reached a point 45 miles from the South Pole. He had no idea of Scott’s whereabouts. Scott had taken a different route slightly to the west, so for all Amundsen knew, Scott was ahead of him. The weather had turned clear and calm, and sitting high on the smooth Polar Plateau, Amundsen had perfect ski and sled conditions for the remainder of the journey to the South Pole. Amundsen noted, “Going and surface as good as ever. Weather splendid — calm with sunshine.” His team had journeyed more than 650 miles, carving a path straight over a mountain range, climbing from sea level to over 10,000 feet. And now, with the anxiety of “Where’s Scott?” gnawing away, his team could reach its goal within 24 hours in one hard push.

And what did Amundsen do?

He went 17 miles.

Throughout the journey, Amundsen adhered to a regimen of consistent progress, never going too far in good weather, careful to stay far away from the red line of exhaustion that could leave his team exposed, yet pressing ahead in nasty weather to stay on pace. Amundsen throttled back his well-tuned team to travel between 15 and 20 miles per day, in a relentless march to 90˚south. When a member of Amundsen’s team suggested they could go faster, up to 25 miles a day, Amundsen said no. They needed to rest and sleep so as to continually replenish their energy.

In contrast, Scott would sometimes drive his team to exhaustion on good days and then sit in his tent and complain about the weather on bad days. In early December, Scott wrote in his journal about being stopped by a blizzard: “I doubt if any party could travel in such weather.” But when Amundsen faced conditions comparable to Scott’s, he wrote in his journal, “It has been an unpleasant day — storm, drift, and frostbite, but we have advanced 13 miles closer to our goal.” Amundsen clocked in at the South Pole right on pace, having averaged 15½ miles per day.

Like Amundsen and his team, the 10Xers and their companies use their 20-Mile Marches as a way to exert self-control, even when afraid or tempted by opportunity. Having a clear 20-Mile March focuses the mind; because everyone on the team knows the markers and their importance, they can stay on track. While it is not the only leadership method we found in our research — Great by Choice delineates fully six sets of findings — 20-Mile March is the crucial starting point.

Financial markets are out of your control. Customers are out of your control. Earthquakes are out of your control. Global competition is out of your control. Technological change is out of your control. Most everything is ultimately out of your control. But when you 20-Mile March, you have a tangible point of focus that keeps you and your team moving forward, despite confusion, uncertainty, and even chaos..

Featured image: cc licensed ( BY NC ND 2.0 ) flickr photo by Blue~Canoe: http://www.flickr.com/photos/bluecanoe/2231497051/